The roots of American cowboy culture can be traced back to the Scottish Highlands, where cattle drovers and herders had long plied their trade. Many Scots immigrants brought their skills and traditions of cattle ranching and horse handling to the American West in the 19th century.

Figures like Jesse Chisholm, who gave his name to the famous Chisholm Trail cattle driving route, exemplified the significant influence of Scottish settlers on cowboy lore and music. Traditional Scottish ballads like “Annie Laurie” became popular campfire songs sung by cowboys to soothe the cattle on long drives.

Beyond the cattle trade, Scottish immigrants also made major impacts in other areas of Western agriculture and sporting culture – introducing sheep ranching expertise, founding early American golf communities with Scottish professionals, and establishing Highland Games competitions on American soil. The deep Celtic passions for livestock, horses, music and athletic contests provided a fertile foundation for the iconic cowboy way of life to take root and flourish in the American West.

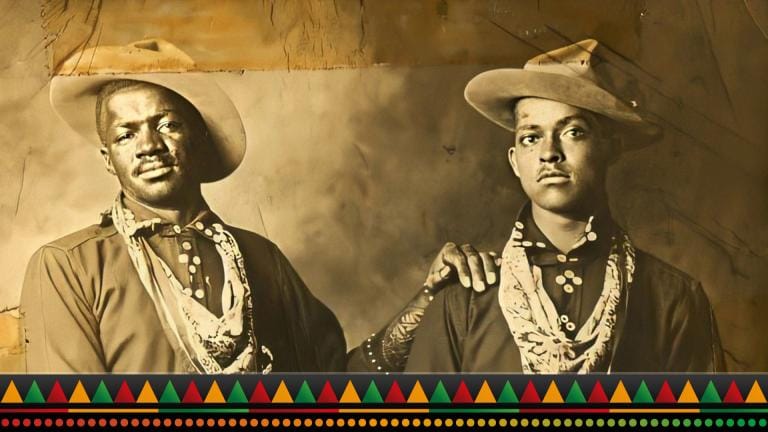

The Unsung Heroes of the Range: Celebrating the Black Cowboys of the American West

In the romanticized lore of the American West, the iconic image of the rugged cowboy has been indelibly etched into the cultural consciousness. From the silver screen to the pages of dime novels, this figure has come to symbolize the spirit of adventure, independence, and the taming of the frontier. However, the true story of the cowboy is far more diverse than the predominantly white narratives that have dominated popular culture. Among the unsung heroes of the range were the Black cowboys, whose contributions were integral to the cattle industry’s expansion and the settlement of the West.

The origins of Black cowboy culture can be traced back to the earliest days of the transatlantic slave trade. Many enslaved Africans brought to the Americas hailed from regions with long-standing traditions of cattle herding and animal husbandry. In West Africa, particularly in regions like modern-day Senegal and Gambia, cattle were not only a source of sustenance but also held significant cultural and spiritual significance.

As these enslaved Africans were forcibly transplanted to the colonies of the New World, their knowledge and skills in cattle handling proved invaluable to the burgeoning livestock industries of the American South and the Caribbean. On plantations and ranches across the region, Black cowboys played a pivotal role in the development of cattle ranching techniques and the establishment of the vaquero traditions that would later influence cowboy culture throughout the West.

With the expansion of the cattle industry westward in the decades following the Civil War, Black cowboys found new opportunities to ply their trade on the open ranges of the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountain West. Estimates suggest that as many as one in four cowboys during the heyday of the cattle drives were African American, with some regions like Texas boasting an even higher proportion.

These Black cowboys faced numerous challenges and adversities, not only from the harsh and unforgiving landscape but also from the deeply entrenched racism and discrimination of the era. Despite these obstacles, many rose to prominence, earning reputations as skilled horsemen, expert ropers, and invaluable members of the cattle crews.

Legends of the Saddle: Iconic Black Cowboys

Among the most celebrated Black cowboys of the 19th century was Nat Love, a former enslaved man who became known as “Deadwood Dick.” Love’s autobiography, published in 1907, offered a rare firsthand account of the life of a Black cowboy, detailing his adventures on the trail and his encounters with legendary figures like Bat Masterson and Billy the Kid.

Another iconic figure was Bill Pickett, widely regarded as the inventor of the rodeo event known as “bulldogging,” in which a cowboy on horseback wrestles a steer to the ground. Pickett’s daring feats and showmanship made him a star attraction in Wild West shows and early rodeos, paving the way for future generations of Black cowboys and cowgirls.

Figures like Bass Reeves, one of the first Black deputy U.S. marshals west of the Mississippi, and Mary Fields, better known as “Stagecoach Mary,” demonstrated the versatility and resilience of Black cowboys in roles ranging from law enforcement to transportation.

Despite the fading of the frontier era, the spirit of the Black cowboy has endured, carried forward by a vibrant community dedicated to preserving and celebrating this rich heritage. Organizations like the Federation of Black Cowboys, based in New York City, have played a vital role in introducing urban youth to the traditions and values of cowboy culture.

Through programs that teach horsemanship, stable management, and responsibility, these organizations offer young people a path to personal growth and empowerment, providing a sense of purpose and connection to a proud legacy that has often been overlooked in mainstream narratives.

In cities across the United States, from Oakland to Philadelphia, Black cowboy clubs and riding associations have emerged as vibrant hubs of community and cultural preservation. Annual events like the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo and the Oakland Black Cowboy Parade serve as powerful reminders of the enduring legacy of Black cowboys, while also inspiring new generations to embrace this rich tradition.

Reclaiming the Narrative

In recent years, there has been a concerted effort to reclaim and amplify the stories of Black cowboys, both past and present. Documentary filmmakers like John Ferguson and Gregg MacDonald have shone a spotlight on contemporary Black cowboys like Jason Griffin, a four-time world champion bareback bucking horse rider, while also exploring the often-overlooked histories of Black riders from the frontier era.

Authors and historians have also played a crucial role in unearthing and preserving the narratives of Black cowboys, challenging the dominant white-centric narratives that have long dominated popular culture. Works like “The Negro Cowboys” by Philip Durham and Everett L. Jones, and “Black Cowboys of the Old West” by Tricia Martineau Wagner, have helped to shed light on the significant contributions of African Americans to the cattle industry and the settlement of the American West.

In the face of oppression, discrimination, and adversity, Black cowboys forged their own paths, carving out spaces of autonomy and self-determination in a world that often sought to deny them their humanity. Their contributions to the development of the American West and the cattle industry were an invaluable role played by African Americans in shaping the nation’s history and cultural identity.

In the words of author and historian Walter Thompson-Hernández, “The Black cowboy is a symbol of resilience, of resistance, of the ability to carve out a space for yourself in a world that doesn’t want you to exist.” It is this spirit of resilience and determination that continues to inspire and empower, reminding us that the true strength of a community lies not in the narratives imposed upon it but in the stories it chooses to tell and celebrate.

Citations:

Scottish Citations: